THE HISTORY OF LICHENOLOGY IN OHIO

The knowledge of Ohio lichens began with a man named Thomas Lea, who resided in the Cincinnati area. Lea was interested in all things botanical and in addition to vascular plants, collected lichens in the Hamilton County area from around 1836 to 1844. His collection of 56 species included many lichens that are now rare, including Lasallia pensylvanica (Wanted (Alive)! LASALLIA PENSYLVANICA. OBELISK 2013, p.11), Umbilicaria muehlenbergii, Pseudocyphellaria aurata (Wanted (Alive)! SPECKLEBELLY LICHEN. OBELISK 2012, p.4) and Usnea longissima. Label information was vague on many of his specimens and these four lichens have not been found again in Ohio and are now presumed extirpated.

His most noteworthy collection was of a small, gray foliose lichen from the Hamilton County Ohio River floodplain. This lichen, later named Phaeophyscia leana, grows on periodically flooded trees, below the high water mark where no other lichens are found. It was known only from the type location which was later destroyed. For over a century Phaeophyscia leana was thought to be extinct. However, in the 1980’s it was found again at several locations along the Ohio River in Illinois and Kentucky. It was also discovered at several locations in Adams County, Ohio, where there are healthy populations in the Edge of Appalachia nature preserves.

There were a number of small lichen collections made during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s but the next milestone in Ohio lichenology was probably the work of Dr. Bruce Fink. He and his students at Miami University collected lichens in southwestern Ohio during early 1900’s. Fink later moved to the University of Michigan and published the authoritative work, The Lichen Flora of the United States (Fink, 1935). This book contains keys and descriptions of 1,578 taxa.

During the 1930’s, Dr. John Wolfe at The Ohio State University collected lichens in the south-central Ohio counties. He also examined Ohio specimens from other herbaria and eventually published A Catalog of the Lichens of Ohio (Wolfe, 1940). This publication, the first comprehensive listing of Ohio lichens, contained 331 taxa, with keys and county records from 67 of Ohio’s 88 counties.

The next milestone was the work of Conan J. Taylor, O.F.M. Father Taylor was a teacher at Bishop Luers High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He had a longstanding interest in lichens and collected in Ohio starting around 1954. During the summers of 1959, 1961 and 1962 he collected several sites from every county in Ohio. This was the first systematic collection of the entire state.

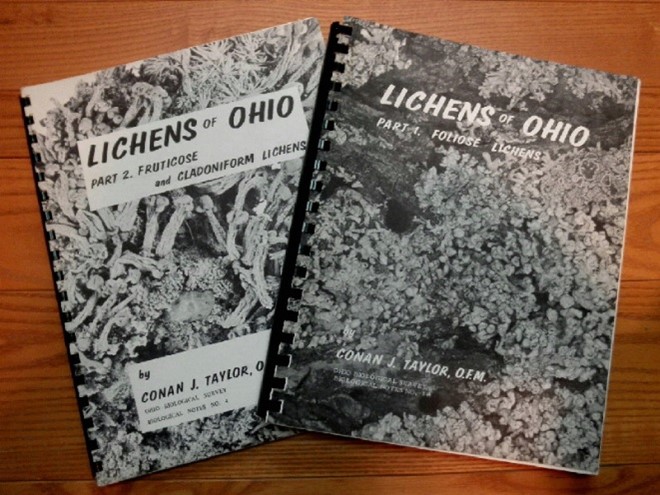

Taylor began the final identifications and compilations of the state lichen flora in 1964. His efforts ended with the publication of The Lichens of Ohio (Figure 1), Part 1 Foliose Lichens (Taylor, 1967) and Part 2 Fruticose and Cladoniform Lichens (Taylor, 1968). This was a state-of-the-art work with very workable keys, detailed descriptions and photographs of each of the 178 foliose and fruticose lichens known from Ohio at that time. His books also included instructions for identifying lichen acids using micro-recrystalization, as well as a very complete pictorial glossary.

Figure 1. Conan Taylor’s Lichens of Ohio. Photo by Ray Showman.

I have a special affinity for Taylor’s books because they were almost brand new when I began studying lichens in 1969. I learned lichen identification from them and used them for a number of years until the taxonomy and nomenclature became outdated.

I was lucky enough to get a job working with lichens and for the next several decades I used lichens as indicators of air quality around coal-burning power plants in the Ohio Valley region (but that is another story). During that time, I also surveyed lichens in a number of Ohio state parks, state forests and state nature preserves. During these outings I met a number of dedicated naturalists, including Don Flenniken, who also had a passion for lichens.

Don and I both realized that Taylor’s books had become outdated by rapidly advancing lichen taxonomy, and in 1990 we published an updated checklist to reflect the current taxonomy and to include new species finds (Flenniken & Showman, 1990).

This collaboration later led to the next milestone in Ohio lichenology. After Don’s publication of The Macrolichens in West Virginia (Flenniken, 1999), we both agreed that it would be nice to have Taylor’s books reprinted (they were by then years out of print) with revised taxonomy and nomenclature and with recent species additions to Ohio.

In preparation for this, Don visited lichen herbaria in the state and annotated many specimens with the correct nomenclature. I did additional field work, visiting some of the lesser collected counties. We had discussions with The Ohio Biological Survey about publication and it was finally decided to do a complete revision rather than a reprint of Taylor’s work. This resulted in a single book covering the Ohio macrolichens, now up to 223 species (Figure 2. Showman & Flenniken, 2004).

Figure 2. The Macrolichens of Ohio. Photo by Ray Showman.

The next high point in Ohio lichenology occurred very soon afterward. Barb Andreas had the vision of starting a group of people interested in Ohio mosses and lichens, with the goal of encouraging the study of these organisms and adding to the knowledge of their distributions in Ohio. An organizational meeting of the Ohio Moss and Lichen Association (OMLA) was held in June, 2004 (Andreas et al. 2005), and as they say, the rest is history.

In the years since then, the OMLA has been successful beyond all expectations. The organization has held forays in 27 sparsely collected counties and has added 340 new macrolichen county records as well as updating many existing records. Members have also added 8 new state records for macrolichens and 5 new state records for crustose species. The known macrolichens of Ohio stands at 238 at this writing.

The OMLA has also been very successful in promoting the study of lichens and bryophytes in Ohio. Membership exceeds 50, including several student members. An annual newsletter, the OBELISK, records activities of the group, with new county records found during forays. It also includes articles on other aspects of bryology and lichenology, written for the nonprofessional. The OMLA sponsors an annual award for the best student paper published in the OBELISK. Member and webmaster Robert Klips also maintains an OMLA website (www.ohiomosslichen.org), which shares our activities and knowledge with anyone who is interested.

In summary, Ohio has had a number of dedicated individuals who have contributed to the knowledge of lichens. From Lea forward to the present, and with OMLA now firmly established, the future seems very bright.

LITERATURE CITED

Andreas, B.K., R.E. Showman and M.H. Zloba. 2005. Formation of the Ohio Moss and Lichen Association, and Report of the First Fall Foray to the Edge of Appalachia Preserve System, Adams Co., Ohio. Evansia 22(3):92-100.

Fink, B. 1935. The Lichen Flora of the United States. The University of Michigan Press. Ann Arbor. 426 p.

Flenniken, D.G. 1999. The Macrolichens in West Virginia. Published by the author. D.G. Flenniken, Sugar Creek, Ohio. 231 p.

Flenniken, D.G. and R.E. Showman. 1990. The Macrolichens of Ohio: A revised checklist. Ohio Journal of Science 90: 130-132.

Showman, R.E. and D.G. Flenniken. 2004. The Macrolichens of Ohio. Ohio Biological Survey New Series Bulletin Vol. 14, No.3. 279 p.

Taylor, C.J. 1967. The Lichens of Ohio Part 1. Foliose Lichens. Ohio Biological Survey Biological Notes No. 3.

Taylor, C.J. 1968. Lichens of Ohio Part 2. Fruticose and Cladoniform Lichens. Ohio Biological Survey Biological Notes No. 4. 227 p. (No. 3 plus No. 4)

Wolfe, J.N. 1940. A Catalog of the Lichens of Ohio. Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin 36 (Vol. VII, No. 1). 50 p.

– Ray Showman