OHIO LIVERWORT DIVERSITY

In Ohio, liverworts aren’t as numerous or important ecologically as the mosses, but they are of great interest to us.

We log them on our forays and an intensive cataloguing effort has been initiated, as described in Barb Andreas in her “Wanted Alive: Liverworts” article in the 2011 OBELISK.

In the summer of 2018 I attended an excellent week-long seminar on liverworts taught by Blanka Aguero at Eagle Hill Institute in Maine. This was eye-opening, and an inspiration to join in the effort to further document our state’s hepatic biodiversity.

Liverworts comprise the phylum Marchantiophyta, which is divided into three classes, two of which are speciose and occur in Ohio. The less numerous of the two, but better known to the general public whose only experience with bryophytes may be through introductory biology texts, is Marchantiopsida, the complex thalloid liverworts. These have a fairly thick body consisting of multiple cell layers that is flattened and lobed. Their shape is the basis for the name “liverwort,” whereby according to the ancient “Doctrine of Signatures” a plant’s resemblance to a specific body part was seen as a divine creator’s hint the plant could be used to treat ailments of that organ. Many Marchantiopsida produce elevated structures that are not, as one would expect, sporophytes, but are gametangiophores, also called “receptacles,” stalks composed of gametophyte tissue within which develop microscopic egg or sperm-producing structures, the gametangia. After fertilization, small and inconspicuous sporophytes develop beneath the female receptacles. The following photo shows a female receptacle with mature sporophytes –the dark fuzzy objects –of Preissia quadrata, a pronounced calciphile seen growing on a limestone ledge at Shoemaker State Nature Preserve in Adams County. The reason the sporophytes look fuzzy is that, intermixed with the spores, there are elongate hair-like cells called “elaters” (inset) that unfurl when the spores are ripe, helping to disperse them.

Much more numerous, and not at all liver-like, are members of the class Jungermanniopsida, most of which are leafy and could easily be mistaken for mosses. Jungermanniopsida also includes some simple thallose liverworts, strap-shaped plants that are thin (mostly one cell layer thick) and lack the elevated umbrella-like gametangium-producing structures found on most of the complex thalloid species. Compared with mosses, liverwort sporophytes are simple and delicate, short-lived affairs, consisting of a dark ovoid capsule (the sporangium) supported by a whitish translucent seta. A typical young sporophyte is shown below. At maturity it would be taller, and the sporangium split into 4 segments.

Here are some of Ohio’s common liverworts, arranged in the categories set forth in an especially useful introductory work, “Liverworts of New England -A Guide for the Amateur Naturalist, by Mary S.G. Lincoln,” published by the New York Botanical Garden Press.

A. Complex Thalloid Liverworts with Elevated Receptacles. The world’s most well-known liverwort is Marchantia polymorpha. Robust and distinctive, in Ohio it is occasionally found on disturbed sites, but is more frequent as a greenhouse weed, hence its appearance in biology classes and textbooks. The photo below was taken at a native plant nursery in Delaware County.

The flat-topped, scallop-edged receptacles are male antheridiophores, while the more deeply lobed drooping-armed ones are female archegoniophores. After fertilization, small inconspicuous sporophytes develop beneath the lobed arms of the archegoniophores.

In some thalloid liverworts, only the female gametangia are on elevated structures, while the male gametangia are clustered in little button-like pads near the tips of some thallus lobes, denoted by the arrow in the photo below of Reboulia hemisphaerica on a limestone ledge in woods alongside the Scioto River in Delaware County.

The most frequently recognized Ohio liverwort (Note the careful word choice here, as it probably isn’t the most frequently seen species.) is undoubtedly a robust snake-skin lookalike called Conocephalum. The taxonomy of Conocephalum is a bit of a mess right now, as various sources will assert either that some or all North American material is Conocephalum conicum (the traditional name by which most people have learned it), Conocephalum salebrosum (a new name proposed by scientists focusing on European material), or might belong to several cryptic species distinguishable only by molecular methods known as “A-type,” “C-type,” and “L-type.” Let’s just call it Conocephalum for now. The photo below, with a lime-loving moss, Timmia megapolitana, was photographed on a damp limestone ledge at Indian Mound Reserve in Greene County. Scratch and sniff! Conocephalum has a most distinctive spicy-citrus aroma. Look for the aromatic liverwort on wet limestone or sandstone bluffs, where it often grows in extensive mats.

Other Ohio genera of complex thalloid liverworts with elevated receptacles include Preissia, Mannia and Asterella.

B. Complex Thalloid Liverworts with Buried Capsules. Complex thalloid liverworts are somewhat spongey, with air chambers in the tissue. In a few principally aquatic species the sex organs, rather than being borne on raised or otherwise evident structures, are buried in some of the air chambers. One of these, Riccia fluitans, grows in interwoven tangles of narrow ribbons floating just beneath the surface of a pond or stranded on mud nearby. This species is a favorite aquarium plant; in the trade it is known as “crystalwort.” The photo below was taken in a shallow pond edge at Calamus Swamp in Pickaway County.

Ricciocarpos natans forms rosettes that float on calm water, often alongside Riccia fluitans and other aquatic vascular plants, especially duckweeds. Like Riccia, it also often grows on mud at the pond edge. The photo below was taken on a shady path adjacent to the buttonbush swamp where the Riccia lives.

C. Simple Thalloid Liverworts. These plants are in most instances ribbon-like, and usually just a few cells thick, smaller and more delicate than their complex cousins. Pallavicinia lyellii is often found in swampy environments on peaty soil. The specimen shown below was found on a well-rotted stump in a vernal pool depression at Garbry Big Woods Sanctuary in Miami County.

C. Simple Thalloid Liverworts. These plants are in most instances ribbon-like, and usually just a few cells thick, smaller and more delicate than their complex cousins. Pallavicinia lyellii is often found in swampy environments on peaty soil. The specimen shown below was found on a well-rotted stump in a vernal pool depression at Garbry Big Woods Sanctuary in Miami County.

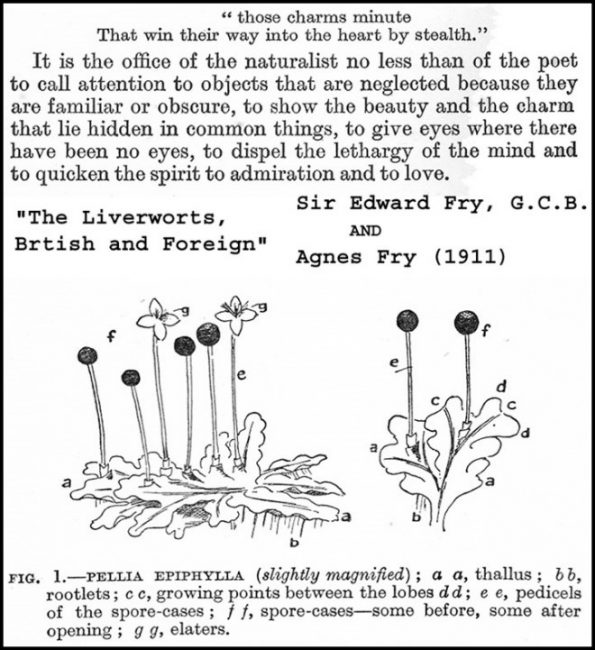

Pellia epiphylla is a large, relatively common simple thalloid liverwort found on bare soil such as road cuts, drainage ditches and streambanks in wooded areas. The individual shown below was seen adjacent to a stream in Shade River State Forest in Meigs County.

Other Ohio genera of simple thalloid liverworts include Blasia, Moerckia, Aneura, Metzgeria, and Riccardia.

D. Leafy Liverworts with Finely Dissected (feathery) Leaves. Unlike mosses, which have leaves that are always simple and often are entire-margined, liverwort leaves are often very elaborate. Some have leaves that are ciliate (inset on photo), for example Ptilidium pulcherrimum. This is a robust species that forms flat mats on logs. The one shown below was photographed at Cuyahoga Valley National Park in Summit County.

Other Ohio genera of leafy liverworts with feathery leaves include Blepharostoma and Trichocolea.

E. Leafy Liverworts with Toothed Leaves and Incubous Insertion. Most leafy liverworts are more or less flat, with two opposing rows of sideways-projecting lateral leaves, along with one row of much smaller ventral leaves. As viewed from the side, the lateral leaves are almost always inserted obliquely, i.e., slanted and overlapping one another Venetian blind style. Like Venetian blinds, which can have the upper edges of the slats either above or below neighboring slats depending on how they are adjusted, leafy liverworts with oblique leaf insertion can either be “incubous,” i.e., with the forward edge of each leaf lying above the next leaf tip-ward, or “succubous,” slanted in the reverse direction. A way to ascertain whether the leaves are incubous or succubous is to imagine a raindrop hitting the plant and assess which way the water would flow after landing on the leaves: backward would be incubous, and forward succubous. This may be clear in the photo below of the most robust and distinctive of our leafies, Bazzania tribolata, as seen on the ground in a hemlock forest at a private nature preserve in Hocking County.

F. Leafy Liverworts with Lobed Leaves and Incubous Insertion. Moss leaves are never lobed. Liverwort leaves frequently are. Lepidozia reptans is a small liverwort found on stumps and peaty soil with leaves that are shallowly palmately 4-lobed, looking a bit like the hands of characters on “The Simpsons.” The picture below was taken in a bog at Great Waas Island Preserve in Washington County, Maine.

F. Leafy Liverworts with Lobed Leaves and Incubous Insertion. Moss leaves are never lobed. Liverwort leaves frequently are. Lepidozia reptans is a small liverwort found on stumps and peaty soil with leaves that are shallowly palmately 4-lobed, looking a bit like the hands of characters on “The Simpsons.” The picture below was taken in a bog at Great Waas Island Preserve in Washington County, Maine.

Another Ohio genus of leafy liverwort with lobed leaves and incubous insertion is Kurzia.

G. Leafy Liverworts with Entire Leaves and Incubous Insertion. Our only genus with this combination of leaf form and insertion is Calypogeia. The most common species here and in Washington County, Maine, where the photo below was taken, is C. mulleriana. In Ohio it is often found on damp sandstone in shaded ravines. Note the gemmiparous shoot, ending in a capitate cluster of 2-celled asexual propagules.

H. Leafy Liverworts with Toothed Leaves and Succubous Insertion. A better analogy for leaf insertion might be roof shingles. With a succubous insertion the rain will not run in. Plagiochila porelloides is a large liverwort, somewhat suggestive of a wrinkled Plagiomnium moss, that is fairly common on vertical rock surfaces, especially near streams. The photo below was taken at Sheick Hollow State Nature Preserve in Hocking County.

H. Leafy Liverworts with Toothed Leaves and Succubous Insertion. A better analogy for leaf insertion might be roof shingles. With a succubous insertion the rain will not run in. Plagiochila porelloides is a large liverwort, somewhat suggestive of a wrinkled Plagiomnium moss, that is fairly common on vertical rock surfaces, especially near streams. The photo below was taken at Sheick Hollow State Nature Preserve in Hocking County.

I. Leafy Liverworts with Lobed Leaves and Succubous Insertion. One of our most common liverworts, Lophocolea heterophylla is easy to see and recognize. It often grows on otherwise barren well-decayed wood, so it stands out visually. The leaves are sharply bidentate, but with the teeth deep enough, and large enough, to be considered lobes. The specimen shown below was growing on a decorticated log at Irwin Prairie State Nature Preserve in Lucas County.

I. Leafy Liverworts with Lobed Leaves and Succubous Insertion. One of our most common liverworts, Lophocolea heterophylla is easy to see and recognize. It often grows on otherwise barren well-decayed wood, so it stands out visually. The leaves are sharply bidentate, but with the teeth deep enough, and large enough, to be considered lobes. The specimen shown below was growing on a decorticated log at Irwin Prairie State Nature Preserve in Lucas County.

Other Ohio genera of leafy liverworts with lobed leaves and succubous insertion are Lophozia, Harpanthus, Nardia, Cephalozia, Cephaloziella, Cladopodiella, and Geocalyx.

J. Leafy Liverworts with Entire Leaves and Succubous Insertion. When they lack reproductive structures, as is often the case, these liverworts are sometimes difficult to separate even to the level of genus. The rectangular-leaved species of Jungermannia and Jamesoniella are the worst! Below, see a more round-leaved species of Jungermannia (which some references list as Solenostoma), J. gracillima. It was observed on thin soil on a sandstone bluff at Conkle’s Hollow State Nature Preserve in Hocking County. Occurring in green as well, the red color of this specimen is an adaptation to growth in open sunlight; several liverworts are known to be variable in this way.

Other leafy liverwort genera with entire leaves and succubous insertion include Mylia, Odontoschisma, Chiloscyphus, and Solenostoma.

K. Leafy Liverworts with Lobed Leaves and Transverse Insertion. Shingles never do this, except maybe in a hurricane, so perhaps the Venetian blinds are a good comparison after all. Let the sun shine in! Liverworts with leaves perpendicular to the stem are not especially numerous. Our best example has such distinctively shaped leaves that you might not even notice the insertion type. This is Nowelia curvifolia, a small dark green (sometimes reddish when in sunny places) wiry plant with leaves that look like billowed sails. The photo below shows it with Lophocolea at Mt. Gilead State Park in Morrow County.

Other leafy liverwort genera with lobed leaves and transverse insertion include Cephaloziella, Tritomaria, Barbilophozia, and Marsupella.

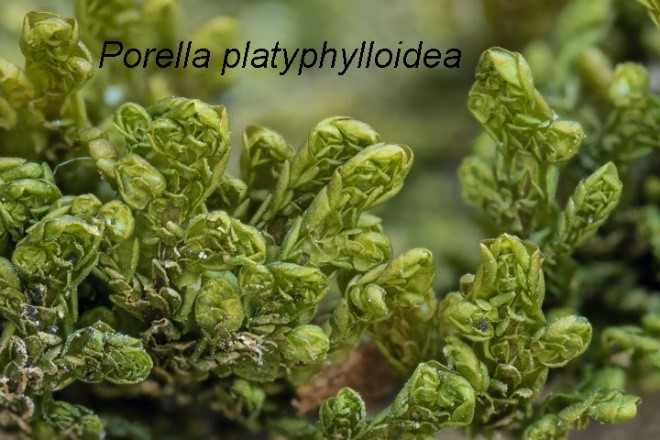

L. Leafy Liverworts with Complicate-Bilobed Leaves, Larger Lobe on Top. These worts have folded leaves! The undersurface of a common species, Porella platyphylloidea, shows considerable intricacy.

That photo was taken at historic Greenlawn Cemetery in Columbus, Ohio where once upon a time somebody made what may not have been not the best choice of building materials for an eternal monument, but is a terrific substrate for bryophytes and lichens. Incidentally, this spot is within shouting distance of the grave of William Starling Sullivant, (1803-1873), the “father” of American Bryology.

Another example is Cololejeunea biddlecomiae, one of our tiniest species, which from any distance except very close appears as an undifferentiated green haze on, typically, a boulder in the woods. It is easily overlooked. The specimen shown below was photographed at Mt. Gilead State Park in Morrow County.

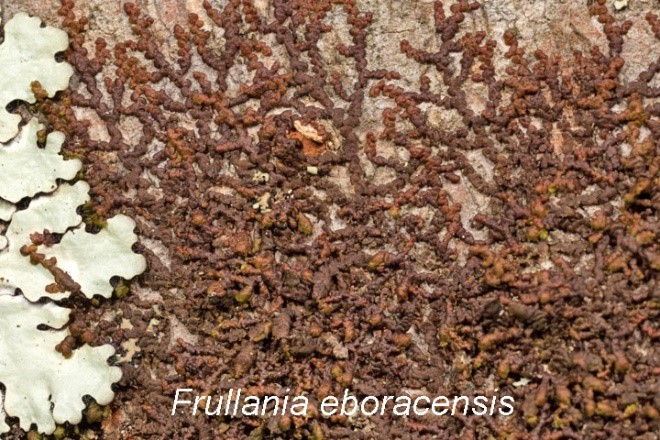

Because it is very common, growing at eye-level on trees throughout the region, Frullania eboracensis has probably been seen by every nature-lover, although perhaps without being recognized as a liverwort.

So common that it has been called Frullania e-boring-censis, this species grows in dark circular patches of wiry stems, tightly adherent, almost lichen-like in aspect. The picture below was snapped in Rothenbuhler Woods State Nature Preserve in Monroe County.

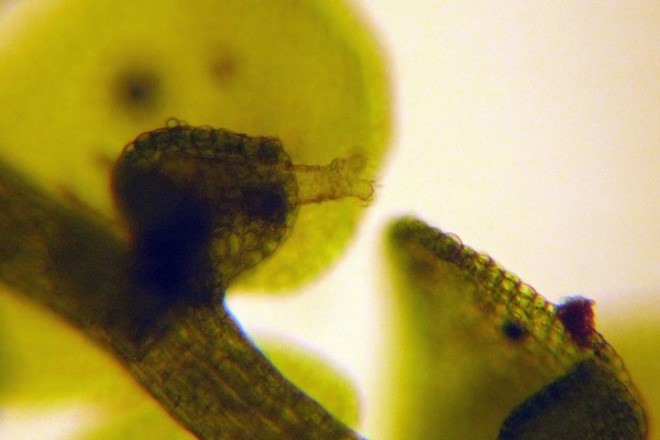

To characterize Frullania merely as having small ventral lobes is an understatement. The lobes take the form of amazing inflated urn-like open-mouthed pouches. In the photo below taken though a compound microscope, a minute but complex animal called a rotifer is seen to have taken residence within a lobe, its crown of cilia extending out the orifice. A rotifer’s cilia beat in rhythmic fashion, setting up water currents that bring food to its mouth. It’s fun to watch. Maybe this liverwort isn’t boring after all.

Other Ohio leafy liverworts genera with complicate-bilobed leaves, larger lobe on top include Leucolejeunea, Lejeunea, Jubula, and Porella.

M. Leafy Liverworts with Complicate-Bilobed Leaves, Smaller Lobes on Top.

Scapania nemorea is common, almost weedy, in a variety of damp or wet shady woodland environments, especially sandstone cliffs. The leaves are round and sharply toothed all around. In addition to the diagnostic leaf orientation and morphology, it often produces distinctive clusters of green gemmae, visible in the photo below, taken at Blackhand Gorge State Nature Preserve in Licking County.

Another Ohio genus of leafy liverworts with complicate-bilobed leaves, smaller lobes on top, is Diplophyllum.

N. Leafy-Thalloid Liverworts. More closely related to the simple thalloid liverworts (i.e., classified with them in the order Metzgeriales), members of the genus Fossombronia are annual plants of exposed soil that have leaf-like ruffled lobes. The species are distinguished on the basis of microscopic aspects of spore ornamentation. The specimen below was photographed on the muddy bank of East Fork Queer Creek in Hocking County.

O. Hornworts. Although they constitute an entirely separate phylum, the Anthocerotophyta, liverwort guides invariably include hornworts as well. It’s a good thing because a book devoted to Ohio hornworts would be terribly skimpy, as we only have four species here. Hornworts are a small group of approximately 100 species worldwide, most of them tropical. Hornworts are unique plants. They have a liverwort-like thalloid growth form. Some harbor colonies of nitrogen fixing cyanobacteria (Nostoc) in chambers in their thalli. The sporophytes have stomata –breathing pores –that are lacking entirely in liverworts, but do occur on moss sporophytes. The spike-like hornwort sporophyte (the basis for the group’s common name) grows in a very unusual manner, by adding cells at the base rather than the tip. Although uncommon, hornworts tend to grow in rather unexceptional situations: road banks, edges of trails, farm fields and wet rocks in woodlands. The hornwort below was photographed on ground that was disturbed for the excavation of a buried natural gas pipeline in Hocking County. It’s a Phaeoceros, one of two quite nearly identical species separated on the basis of sexuality: the sexes are separate in P. laevis, whereas P. carolinianus is cosexual.

The other Ohio hornwort genera are Notothylas and Anthoceros. –Bob Klips