Inroduction to Field Bryology

“I don’t know my mosses!”

Have you ever said “I don’t know my mosses”? Many skilled botanists who have managed to tackle other challenging plant groups such as sedges, ferns or the Aster family think of mosses as being beyond their reach. Not so! They’re just small, that’s all. With a couple of microscopes, some fine-pointed tweezers, and Howard Crum’s excellent manual Mosses of the Great Lakes Forest, you can learn how to identify these charming plants.

The place of mosses in the plant kingdom

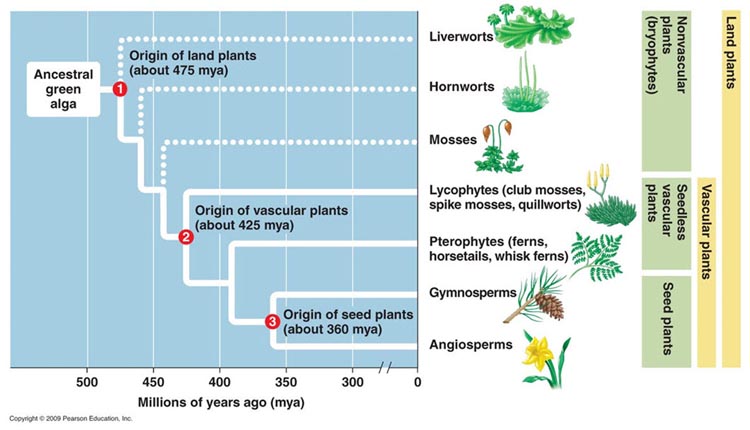

The plant kingdom is divided into a number of phyla (which are sometimes called “Divisions”). There are about 10 to 13 phyla recognized, the exact number depending on how much the particular authority lumps, or splits, the plant kingdom. The figure below, taken from a really good introductory biology textbook, Biology: Concepts and Connections by Campbell, Reece, Mitchell and Taylor, shows a simplified phylogeny (evolutionary tree) of plants. Notice that the group labelled “bryophytes” evolved before the other plant groups, i.e., prior to the development either of vascular tissue or seeds.

Evolutionary tree of the plant kingdom, as depicted in an excellent college biology text.

Moss Life Cycle

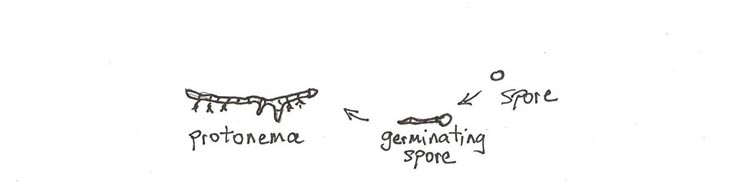

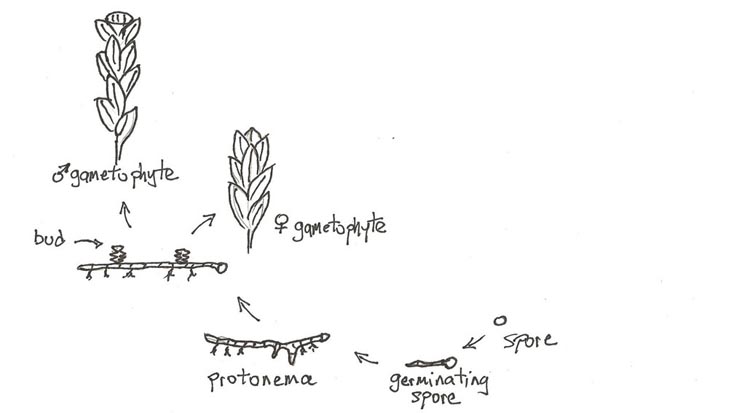

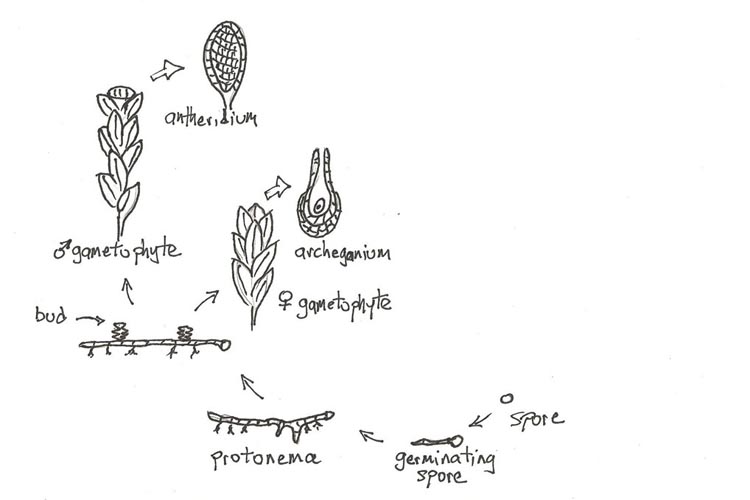

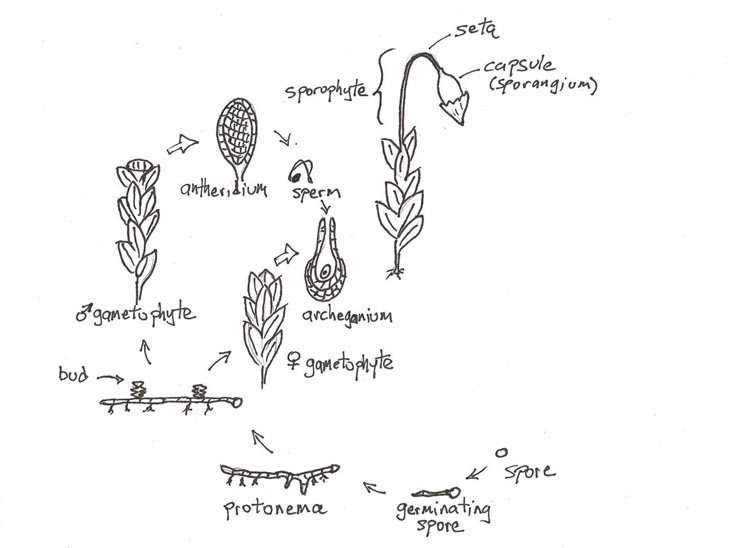

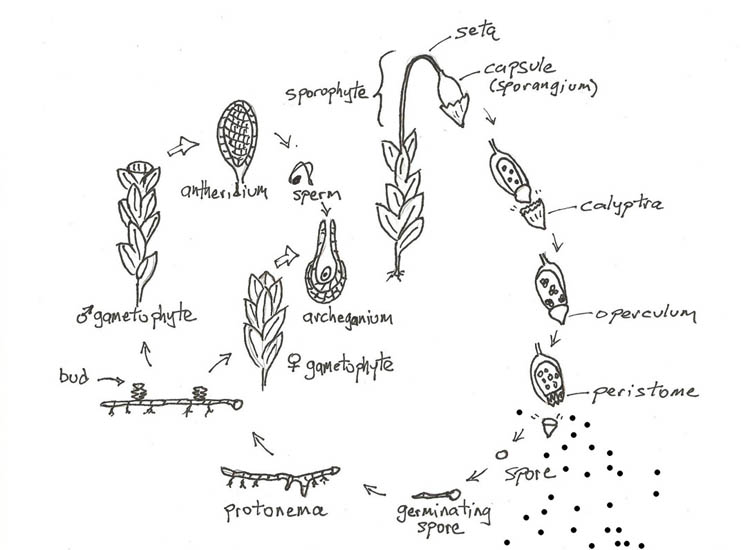

A moss SPORE germinates and develops into a green mass of thin threads called the PROTONEMA. The protonema, a phase in the gametophyte stage of the life cycle, resembles a filamentous green alga.

Note: The moss life cycle figures here are redrawn with slight modification from A Laboratory Manual for Botany by Margaret Balbach and Lawrence Bliss (2002).

Below, see the protonema of a quick-growing, short-lived little cushion moss (acrocarp) of open sites, Physcomitrium pyriforme, with the leafy phase of the gametophyte beginning to spring forth from it.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE to see MATURE Physcomitrium pyriforme

A moss protonema is the threadlike early form of the gametophyte stage of the life cycle.

The moss GAMETOPHYTE is the dominant stage in its life cycle: persistent, photosynthetic, and assimilating resources from the environment. It’s what you’d readily recognize and call “a moss.”

Many mosses, much of the time, are present only as gametophytes, and, thankfully, in many instances they may be identified using gametophytic features alone. Below are some example of moss gametophytes.

Campylium chrysophyllum is a carpet moss that is common on the ground in open woods. Note the widely spreading leaves.

Campylium chrysophylum.

Gametophytes of the closely related cushion moss genera Mnium and Plagiomnium have fairly broad leaves.

Gametophytes of two cushion mosses.

Left: Mnium hornum. Right: Plagiomnium ciliare.

The carpet moss genus Brachythecium is often seen without sporophytes, making identification difficult.

Brachythecium is a common genus of mainly woodland carpet mosses.

Entodon cladorhizans is a shiny carpet moss.

At the ends of some of the branches of sexually reproducing mosses, clusters of tiny GAMETANGIA (gamete-producing structures) develop, which are over-topped or encircled by the surrounding uppermost leaves. The male (sperm-producing) gametangia are tiny sac-like structures called ANTHERIDIA, each of which produces many SPERM. The female ARCHEGONIA are tiny and flask-shaped with an opening at the top for sperm to enter and a single EGG inside, down at the bottom.

There’s a little brick wall in front of a residence in Columbus (also known as “my house”) upon which grow two mosses of somewhat similar overall form that nonetheless reproduce in very different manners. Orthotrichum pumilum (left side of the photo below) is sexual, with gametangia, gametes, sporophytes and spores, whereas (right side of photo) Syntrichia papillosa is wholly asexual, reproducing only by means of small easily detached spherical gemmae covering the middle portions of most leaves.

Two mosses on a wall. Left: Orthotrichum pumilum. Right: Syntrichia papillosa.

Two mosses on a wall. Left: Orthotrichum pumilum. Right: Syntrichia papillosa.

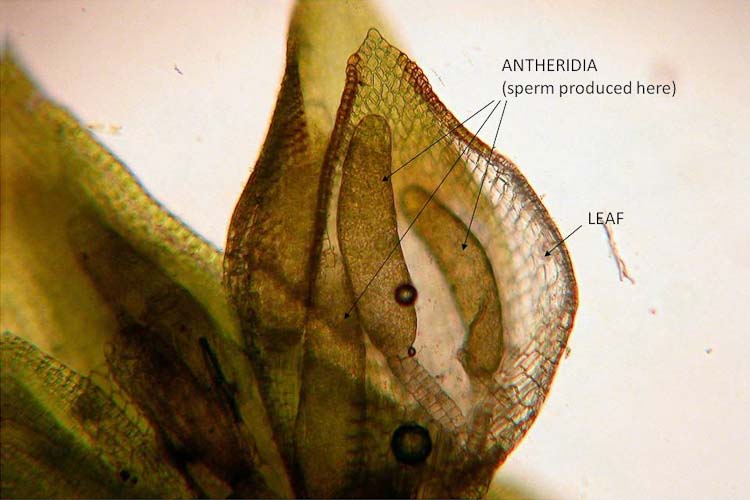

Examination through a compound microscope at 100X of the tips of this sexually reproducing Orthotrichum in early March revealed gametangia. The antherida –male gametangia –are cylindric sacs within which sperm are produced by mitosis.

Antheridia are male gametangia.

The female ARCHEGONIA are flask-shaped, with an opening at the top for sperm to enter, and a single EGG (produced by mitosis) inside at the bottom.

Archegonia are female gametangia.

With the help of a raindrop or simply by swimming through a film of water, sperm find their way into an archegonium and fertilize the egg there to begin the diploid sporophyte phase of the life cycle. The male plants of some species of mosses have their antheridia clustered and surrounded by a circle of leaves that act as a “splash cup” to enable sperm to be broadcast when the cup is struck by a raindrop. Here are two examples of splash-cup males. First, see Plagiomnium ciliare, a cushion moss that grows on boulders in shady places.

Plagiomnium ciliare male plants have splash cups to disperse sperm.

Atrichum angustatum is a cushion moss that grows on newly disturbed soil in open woods.

Atrichum angustatum male plants have splash cups to disperse sperm.

After an egg is fertilized (thus becoming a diploid ZYGOTE) , it develops by mitosis into a multicellular diploid sporophyte.

The moss sporophyte is a comparatively simple structure typically resembling a tiny golf club stuck onto the maternal gametophyte that produced it. It remains attached to the maternal gametophyte (“Mom”) for its whole life, deriving most of its nutrition from “her.”

Bryum lisae variety cuspidatum is a moss that has a prominent sporophyte stage in its life cycle.

Bryum lisae var. cuspidatum is a cushion moss (acrocarp) with tall sporophytes.

The moss sporophyte consists of a SPORANGIUM (often called the “capsule”) within which spores are produced (by meiosis) supported by a slender stalk, the SETA. When it is young, the sporophyte is protected by a hat-like covering, the CALYPTRA. The calyptra, composed of maternal gametophyte tissue, is a remnant of the archegonium. Until the spores are mature, the mouth of the capsule is covered by a cap-like lid, the OPERCULUM, which eventually falls off to allow spore release. Spore release is typically regulated by one or two rings of teeth around the mouth of the capsule, the PERISTOME.

The Orthotrichum moss on the brick wall that displayed its antheridia and archegonia in early March, by late March had immature sporophytes. Note that in this species, the supporting stalk –the seta –is so very short that we see only the sporangium, nestled among the upper leaves.

Three immature Orthotrichum sporophytes. Two of them are covered with the calyptra.

The central one has shed its calyptra, and the operculum (lid) is visible.

The asexually-reproducing moss Syntrichia papillosa is predominant as well.

In April, the Orthotrichum mosses on the wall have shed their opercula, and are releasing spores. The area around the mouth of the capsule, called the “peristome,” is encircled by a ring of teeth.

Mature Orthotrichum sporophytes, with a peristome of 16 segments.

The asexually-reproducing moss Syntrichia papillosa is predominant as well.

For another example of a moss with short sporophytes growing on a stony substrate, lets visit a small old rural cemetery in Marion County, Ohio. In the center of the picture below, there is a small flat grave marker flush with the ground that is covered with moss.

Thew Cemetery in Marion County, Ohio.

Rural cemeteries are great moss and lichen hunting grounds!

The moss is a little-branched carpet moss that grows in blackish tufted mats: Schistidium rivulare. The photo below show what it looked like in February, with capsules immature, each topped by a small smooth pointed calyptra split equally down the side in several places.

The moss Schistidium rivulare in mid-February, with immature capsules.

By mid-April the Schistidium capsules are mature and releasing spores.

Schistidium rivulare with mature sporophytes, releasing spores, in mid-April.

Sometimes moss sporophytes are quite intricate, bearing two concentric rings of teeth on the peristome. The teeth open and close purely in response to atmospheric humidity (they are the non-living remnants of cell walls), and so enable the release of spores under the correct conditions (usually, but not always, when it is dry).

Aulocomnium heterostichum capsules bear two rings of teeth on the peristome.

“Fire moss,” (also called “cord moss”), Funaria hygrometrica has distinctive golf-club driver-like sporophytes, with an inversely pera-shaped, asymmetric sporangium.

Sporophytes of Funaria hygrometrica are tall, with an asymmetric, slightly nodding capsule.