Crum Bryological Foray, June 2-5, 2014

It sounded intriguing, and it was: an invitation to join a bunch of uber-friendly professional, amateur, and, We were based at the lodge at Blackwater Falls State Park in Davis, West Virginia. It was the customary setup for a several-day bryological foray: field tripping in the daytime, followed by lovely evenings spent identifying our finds in a field lab set up in a conference room. There were lots of microscopes set up on folding tables, an arrangement sometimes known as “heaven.”

On Monday we visited a sugar maple-yellow birch-eastern hemlock-red spruce open woodland in Canaan Valley Resort State Park. Like all the places we visited, this park is in Tucker County. We hiked along the Blackwater River Trail. .

A branch-crotch of a sugar maple tree was home to a seldom-collected moss, Anacamptodon splachnoides (family Campyliaceae). Anacamptodon is called the “knothole moss” for its tendency to occur on moist wood. In 2007, bryologists Donald Davis and Ronald Pursell published in Evansia the results of their concerted effort to locate this species, principally in Pennsylvania. They found that it indeed occurred most often in knotholes (11 out of 24 collections), followed by several instances on the quite similar substrate types of moist decayed hollows or crevices, and limb/trunk crotches. Three of their specimens were found atop a bracket fungus, Oxyporus populinus, also known as the “mossy maple polypore.” (In 1966, however, Aaron Sharp and Lewis Anderson collected Anacamptodon from a most unusual spot –a vertical moist rock face in the Great Smokey Mountains of Tennessee!)

Both the genus and specific epithets are in reference to the capsule. “Anacamptodon” refers to the bent back (when dry) peristome teeth, while “splachnoides” means resembling Splachnum, a nifty moss that grows exclusively on dung. The resemblance, a slight one, is in the peculiar manner in which the capsule is constricted below the mouth.

There is a beautiful marsh here.

The marsh is packed with mosses, including members of the genus Sphagnum, the principal genus in a class of mosses, the Sphagnopsida, situated near the base of the Bryophyta evolutionary tree alongside a few other small groups that either lack peristome teeth altogether or have peristomes of a markedly different construction than do the more typical mosses in the class Bryopsida. Peat mosses have several unique features, including the the occurrence of branches in tufted bundles (capitula) at the top of each stem.

Here we see “tree moss,” Climacium americanum (Climaciaceae) mixed with the peat moss, and seeming to be mimicking it.

A fir tree was the substrate for common antler lichen, Pseudevernia consocians. Irwin Brodo, in Lichens of North America, mentions that a closely related European species of Pseudevernia is heavily collected for use in the perfume and cosmetic industry.

The Freeland Boardwalk within Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge (We didn’t have permits to collect there but birds are usually the main attaction on the boardwalk).

Common haircap moss, Polytrichum commune (family Polytrichaceae) occurs in Ohio but, being a denizen mainly of wet acid open places, is quite scarce in most of the state, which is highly forested and/or has alkaline soils. It was thus a thrill to see dense hummocks and swards of this robust moss.

On Tuesday we stayed close to home, in Blackwater Falls State Park. We hiked the Yellow Birch Trail/Allegheny Trail. This is a hemlock-red spruce wet forest with scattered sugar maple and yellow birch trees with occasional sandstone outcrops and boulders.

One of the best mosses we saw is a boreal species that’s quite rare in Ohio but more common here in The Mountain State. Occurring on humus and logs in coniferous forests, this is “knight’s plume moss,” Ptilium crista-castrensis (family Hypnaceae). Looking like miniature ostrich-ferns, the species can be told from the somewhat similar brocade (Hypnum) and fern (Thuidium) mosses by its more upright growth form and, in the case of Thuidium, its once-pinnate, rather than 2-3 pinnate branching pattern.

Through the microscope, the longitudinal folds (plications) of the plume moss leaves are evident.

A shiny pleurocarp moss was abundant on the ground and tree bases; this is satin moss, Brotherella recurvans (family Sematophyllaceae). In the field, look for a flat braided appearance, especially shiny and golden.

Through the microscope, look for a diagnostic trait of the Sematophyllaceae: large thin almost balloon-like alar cells (the cells at the outer corners of the leaf base).

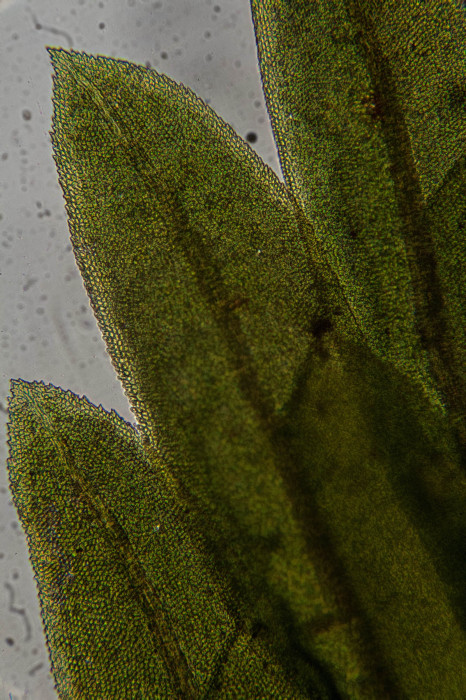

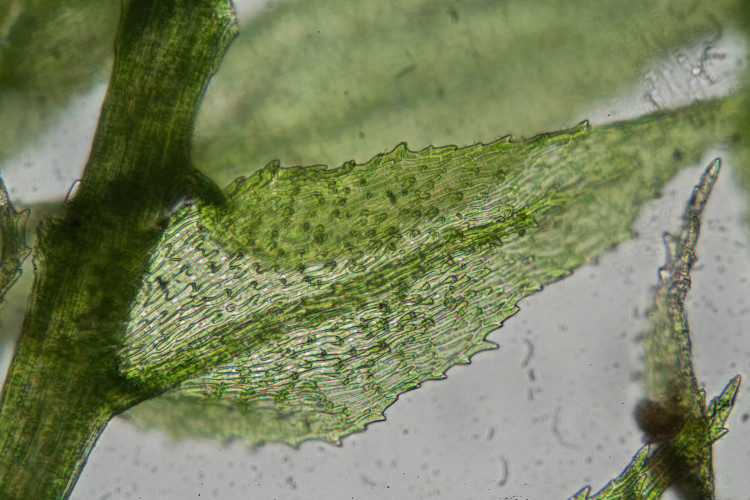

On thin soil over rocks, we found fan pocket moss, Fissidens dubius (family Fissidentaceae) to be amazingly abundant. Fissidens is flat, very flat. Nearly all mosses have leaves arranged in a tight spiral around the stem. Many mosses are somewhat flat (complanate) only because their stems and branches are compressed dorsiventrally, as if they were ironed or stepped on. However, a few moss genera have leaves that are actually arranged in two straight rows directly across from one another. Fissidens is such a two-ranked genus. (Thirteen species of pocket moss occur in Ohio, several of which are very common.)

Fissidens leaves have another peculiarity. Like the leaves of an iris plant, the base of each leaf that faces towards the stem apex is split, forming a pocket-like groove that clasps the lower base of the leaf just above it. The arrangement is suggestive of the way in which an equestrian’s legs clasp a horse, and so the plant is said to have leaves that are “equitant.” This species is distinguished in part by its leaves having a pale margin.

We enjoyed lunch at the Blackwater Falls State Park, Pendleton Point Picnic Shelter. This is an open area with scattered bigtooth aspen trees.

In spots the ground was covered with sand-loving Iceland lichen, Cetraria arenaria. Iceland lichens have a growth form that straddles the border between fruticose (shrubby) and foliose (leafy), and may be best described as “upright foliose.”

On Wednesday we explored the Red Creek Trail at the Dolly Sods Wilderness portion of Monongahela National Forest. This is a humid mixed hardwood-hemlock forest with acidic rock outcrops and a few grottos with traces of calcareous rock.

Dark little grotto.

Flakea papillata, a foliose/squamulose lichen within a monotypic genus in the family Verrucariaceae that grows on moist sandstone deep in the dark recesses of such places, predominantly in tropical areas.

Keeping Flakea company were a few mosses, including another shiny pleurocarp with the courtesy to be identifiable, through the microscope at least. This is grass-colored moss, Bryhnia graminicolor (family Brachytheciaceae).

What makes Bryhnia distinctive is its leaf cells. Long and narrow, they are papillose (extending upwards as pointed projections) at their ends, in the manner of warped up-curled floorboards you might find in a neglected an old house.

The calcareous element in this grotto is evidenced, perhaps, by the occurrence of a typically limestone-loving species, tall tornado moss, Tortella tortuosa (family Pottiaceae).

Our two common species of tornado moss –T. tortuosa and T. humilis — can be a bit difficult to distinguish from one another. This one has especially tortuously long-pointed leaves.

The family Orthotrichaceae includes mainly epiphytic, tufted pleurocarps which are so little-branched that they appear to be acrocarps. The two principal genera in our area are the bristle mosses (genus Orthotrichum) and the tuft mosses (genus Ulota). The trees of Tucker County, West Virginia are home to the most profuse growth imaginable of the aptly-named crispy tuft moss, Ulota crispa. Here’s a photograph of that curly-leaved beauty as seen in Ohio earlier in the year.

Rock tuft moss is a much less common Ulota with leaves that are not at all crisped. It has the general appearance of an Orthotrichum, but microscopic features of the leaf cells, and the emergent sporophyte with a hairy calyptra, taken together, reveal its true affinity.

Threadbare moss, Anomodon tristis, is a very thin pleurocarp that looks like tiny locks of green hair growing high on the bark of trees.

The name tristis means “sad” or “mournful.” Let’s call this “sad moss” from now on. That being said, it looks a lot less sad when it’s hydrated. Let’s call this “happy moss” from now on.

The final day of the foray was also spent at the Monongahela National Forest, mainly along a trail from Forest Service Road 75 along the boundary of Dolly Sods Wilderness to the confluence of Alder Run Bog and Fisher Spring Run Bog. This was a nutrient-poor sedge poor fen, that we accessed along a mixed hardwood-conifer forest trail.

The trail to the fen has open areas with nice mosses and lichens. One of these is pink earth lichen, Dibaeis baeomyces, a common and widespread eastern species that has an extensive white, crustose, ground-covering primary thallus. Extending above the ground are erect stalks capped by pinkish turban-shaped apothecia. Many members of the huge genus Cladonia are like this, except that the Cladonia primary thallus is composed of little squamules having a more foliose aspect.

Atrichum oerstedianum…

The fen was magnificent! In addition to the sedges, Sphagnum and spruces, our terrific WV DNR guides pointed out that this is the southernmost natural occurrence of red pine, Pinus resinosa. Those are red pines in the foreground.

The spruces were adorned with some interesting lichens. A small gray foliose lichen with narrow lobes, covered with coarse isidia on all but the lobe tips, this appears to be salted starburst lichen, Imshaugia aleurites.

This pure brown twig-inhabiting lichen, abundantly beset with apothecia, is chestnut wrinkle lichen, Tuckermanopsis sepincola.

A wildflower that seemed to be everywhere we were in Tucker County WV this first week in June was bluets, Hedyotis caerulea (family Rubiaceae).

Our lunch spot was Bear Rocks along Forest Service Road 75. One of the DNR people mentioned that substantial numbers of golden eagles spend the winter here!

The rocks are great substrate for lichens, including this most conspicuous “plaited rock tripe,” Umbillicaria muehlenbergii. As reflected in the name, rock tripes are among the more edible of the lichens, although they are mostly just survival food. In Lichens of North America, Irwin Brodo mentions that the Nihitahawak people of Saskatchewan used pieces of U. muehlenbergii as an ingredient in a thick, stomach-soothing fish broth.

Weissia controversa (family Pottiaceae). .