A Snapshot of Ohio Lichen Diversity 129 Years Ago:

The Kellerman Displays for the 1893 Chicago Exposition

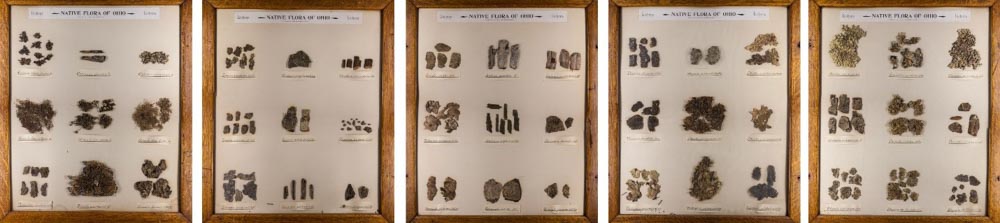

Most of the specimens at the Ohio State University Herbarium (OS) are tucked neatly into cabinets, not on display. Adorning one long wall are what at first glance look like pictures, artfully arranged, each with a wood frames and glass front. A close look, however, reveals they are not paintings or any other type of renderings but are in fact real, once-living, plants and fungi.

Framed specimens at The Ohio State University Herbarium

The displays are quite pretty and they’re obviously rather old, but I only recently stopped to consider just how old they are, or how they came into being. A modern interpretive sign explains that they, along with larger, more intricate panels of Ohio trees, were assembled for display at the World’s Columbian Exposition, a big world’s fair held in Chicago for six months in mid-1893.

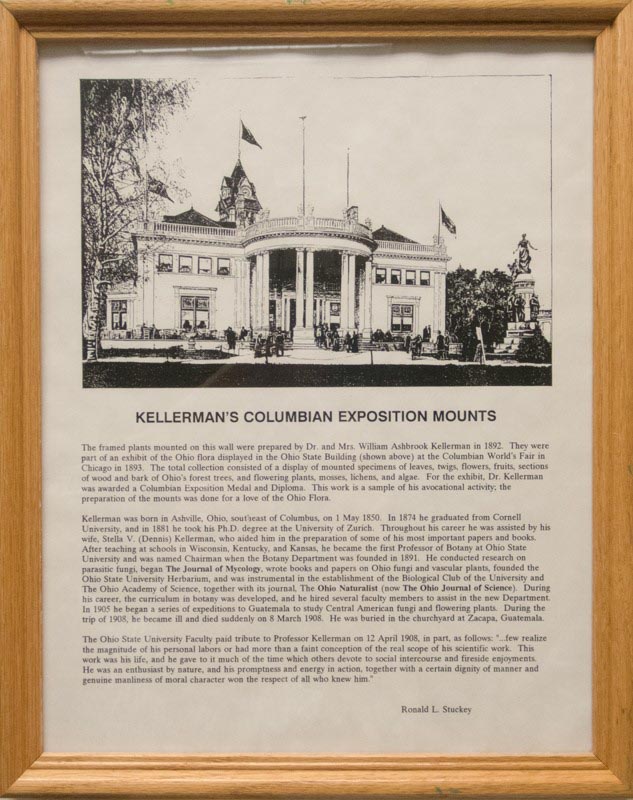

Write-up by Ronald L Stuckey about Kellerman’s Columbian exposition mounts

At the top of each 18 x 22-inch panel is a printed heading “Native Flora of Ohio,” and beneath that, in ornate old-style penmanship, are the words “Prepared by Professor and Mrs. W. A. Kellerman.” William A. Kellerman and Stella V. Kellerman were botanists (William was a mycologist as well) who were remarkably energetic and wide-ranging in their scientific interests. Making these panels was an appropriate hobby for people whose lives revolved around plants and fungi.

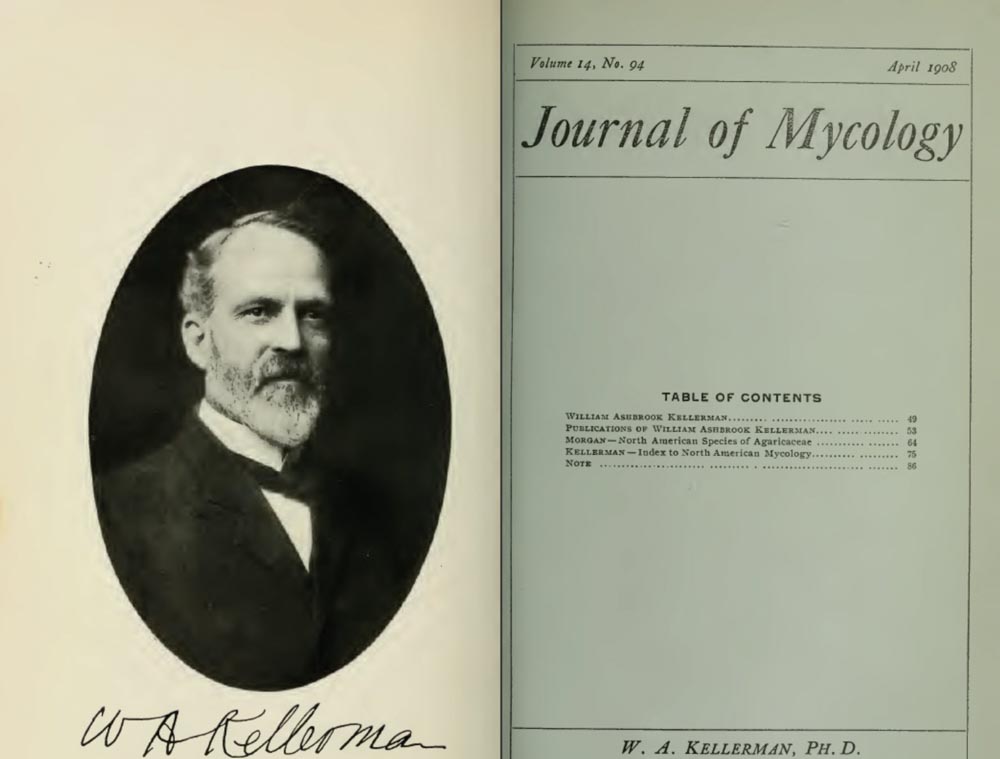

Photo of W.A. Kellerman in the Journal of Mycology

An Ohio native born in 1840, William Kellerman attended Cornell University for undergraduate studies and later received his Ph.D. from the University of Zurich, Switzerland. He taught in schools in several states near Ohio, eventually returning home to become OSU’s first botany professor and Chairman of the Department of Botany when it was formed in 1891. That same year, he established the Herbarium in a building aptly named “Botany Hall” that unfortunately no longer exists on OSU’s oval. Since then, the Herbarium has moved twice, first to the also aptly named “Botany and Zoology” building (now Jennings Hall) and then to its present location as part of the Museum of Biological Diversity on OSU’s West Campus. While his principal research interest was rust fungus diseases of crops, Kellerman’s numerous works on the flora of the regions where he lived reveal an extraordinary breadth of knowledge. Not just an ivory-tower academic, he produced, in collaboration with his wife, several works intended principally for use by teachers, and he was the principal author, beginning in 1894 and subsequently updated several times, of a catalogue of Ohio plants. Sadly, while Kellerman was on a research trip to study fungi in Guatemala, he contracted a fever (most likely malaria) from which he died in 1907.

Mrs. William A. Kellerman.

From the Portrait Archives, The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Stella Victoria (Dennis) Kellerman, also Ohio-born, was 5 years younger than William, whom she met in 1867 while a student at an academy in Fairfield County where he briefly taught before going off to Cornell. After both received their degrees (hers a “Mistress of Letters” from an unknown women’s academy) the couple married in 1876. Their honeymoon was at the United States Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia, which may have provided inspiration for them to participate so fully in the Columbian Expedition. Stella was an accomplished botanist and artist/illustrator who produced nearly 300 original drawings for her husband’s textbook Elements of Botany (1883), the preface to which includes the words “I have been assisted by my wife in the entire preparation of this book, and to her equally with myself is to be attributed any merit that it may contain.” She had a particular interest in leaf shape variation in vascular plants, publishing over 20 scientific papers on that topic. She also developed theories on the origin of corn. Working as a team, the Kellermans updated the aforementioned botany textbook, and produced a Spring Flora book in 1895. They collected specimens for the fledgling State Herbarium (now the OSU Herbarium), focusing on non-indigenous species found in Ohio. An alien plant checklist co-authored by them is aptly described by botanical historian Ronald Stuckey (1992) as being “of fundamental importance in providing base-line data which all subsequent historical studies of plant invasions into Ohio had to take into account.” One of 5 female charter members of the Ohio Academy of Science, Stella served as its vice-president for two terms, and regularly gave presentation at their annual meetings. After William’s untimely passing, Stella discontinued her botanical studies, but stayed very active in civic and scientific clubs and organizations, including one that she helped found, the Women’s National Science Club.

The panels are an interesting snapshot of the flora of Ohio. While aesthetics and enthusiasm for particular plants may have played a major role in their selection by the Kellermans, the panels were indeed portrayed to fairgoers as indigenous representatives of our flora. As there have been substantial changes in the composition of our vegetation, especially for such pollution and disturbance-sensitive organisms as lichens, they arouse curiosity about the past versus present status of these organisms.

There doesn’t seem to be a strict organization scheme for the lichen panels; they’re not in alphabetical or taxonomic order, except that one panel consists mostly of crustose species, while the few fruticose ones represented are grouped together, sharing space with some foliose ones. I suspect that the paucity of fruticose types is attributable to the display method only being suitable for specimens having dorsoventral morphology, i.e., foliose lichens, and crustose ones with attached substrate.

Each panel includes 9 specimens, with handwritten labels. The classification of lichens has undergone substantial change in the past century and a quarter, hence many of the names written by the Kellermans are not in use today. Fortunately, an on-line database “portal,” called “Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria” exists. This is a searchable aggregation of specimen records for lichens residing in collections in institutions spanning the continent. Because the specimens are entered by collections managers using whatever data are on the labels, the site takes into account name changes, so that a search for records using an obsolete name will generate a list of all specimens for that species irrespective of what name is on the herbarium packet. This useful “redirection” feature of the portal facilitated the interpretation of this set of 128-year old names, bewildering at first because many are unfamiliar to a 21st-century lichen enthusiast.

The distribution and ecology of lichens in Ohio is well described in The Macrolichens of Ohio by Ray E. Showman and Don G. Flenniken, published in 2004 by the Ohio Biological Survey, and by recently revised distribution maps presented on our Ohio Moss and Lichen Association web site. The status of the lichens over a broader geographical area is set forth in the monumental book Lichens of North America by Irwin M. Brodo, Sylvia D. Sharnoff and Stephen Sharnoff, published in 2001 by Yale University Press, along with an updated companion volume by Brodo published in 2016 by the Canadian Museum of Nature, Keys to Lichens of North America: Revised and Expanded. The data sets used to produce the maps in The Macrolichens of Ohio and their updates on the OMLA web site did not apparently draw upon all the specimens that reside in herbaria that are members of the Consortium of North American Lichen Herbaria. Conversely, the authors of the Ohio work may have had access to records that are not included in the portal. Consequently there are some differences, especially with old records such as these, between what comes up from CNALH search results and the published distribution maps. Moreover, and very importantly, the CNALH records are not necessarily in all instances correct, identification-wise. They only reflect what the specimen packet labels say. For simplicity, the specimen record data examined and reported here are all from the CNALH portal, searched during a one-week period spanning late November to early December 2021.

The Lobaria Panel

–an interpretation of the specimens–

Kellerman Lobaria Panel

The first panel to catch my eye houses a group of mostly rather large foliose lichens, including several “lungworts,” members of the genus Lobaria. These are robust broad-lobed species found on bark. Let’s home in on the 9 lichens on this panel. From upper left to lower right, they are the following:

Physcia obscura, which synonymizes to Phaeophyscia orbicularis (Necker) Moberg. This “mealy shadow lichen” has 2468 North American specimen records on the portal, 130 of which are from Ohio, distributed among 47 counties. The most recent Ohio collection was by Tomás Curtis in 2020, from Pickaway County. This is not surprising, but there’s a catch. Before the half-dozen 21st-century collections by him, there were none after the 1970’s. Many were made during the 1950’s and 1960’s by the very active mid-20th-century lichenologist Fr. Conan J. Taylor. The conspicuous lack of collections by several especially active investigators whose work is otherwise well represented in regional herbaria was explained by OMLA co-founder Ray Showman in a “Wanted (Alive)” article in the 2010 OBELISK where he explained that until about 1978 the name Phaeophyscia orbicularis was used in a broad sense to include several shadow lichens, some quite common, that are now recognized as distinct species. The name Phaeophyscia orbicularis now applies to a distinct species found mainly in the western and northern parts of North America. At the time of the writing of the OBELISK article the only confirmed Ohio records for authentic P. orbicularis was from material collected by Paul Kaucher from one Adams County nature preserve in 1978 and 1979. At that time the status of Phaeophyscia orbicularis was unknown and it appeared on an Ohio “Lichen Watch List” with hopes that it would be discovered, Happily it was. Most likely though, the Kellerman’s specimen behind the glass is just the common “powder-tipped shadow lichen,” Phaeophyscia adiastola.

Physcia pulverulenta (Schreb.) Hampe ex Fürnr. (no common name) has only 192 North American records, including 9 Ohio specimens (5 counties). There are no North American records past 1978, and the last OH one was made in 1893 by Ernest Everett Bogue from Franklin County.

Bogue is remarkable for the large number of lichen specimens of his, 1161, that reside in North American Herbaria, and for the fact that nearly all of them are from Ohio. These were collected during the years 1891-1895, while he was a student at Ohio State University, receiving first a Bachelor of Science in Horticulture and Forestry (1894) and then, also from OSU, a Master of Science in Entomology and Botany (1896). Those dates are contemporaneous with Kellerman’s tenure at OSU, thus Bogue was an associate of Kellerman, perhaps even his student. The photo below is from William J. Beal’s 1915 History of the Michigan Agricultural College; and biographical sketches of trustees and professors, posted on a web site devoted to the history of East lansing Michigan authored by Kevin Forsyth.

E.E. Bogue.

From observing an image (on the portal) of a specimen label that references a variety leucoleiptes, images of other specimens on the portal, substrate data referencing bark and limestone rock, and the framed specimen itself, I suspect this taxon is what would nowadays be called Physconia leucoleiptes, a fairly common “frost lichen” for which there are 57 Ohio records, the most recent by Tomas Curtis in 2020 from Fulton County.

Sticta amplissima, when searched for on the CNALH portal redirects you to Ricasolia amplissima (Scop.) De Not. (until very recently known as Lobaria amplissima (Scop.) Forss.). This is a bit of a puzzle. There are 280 North American specimens for this lichen, 15 of which are Ohio ones (from 7 counties). There are no Ohio records records after a 1910 collection by E. Lucy Braun from Butler County that was determined by Bruce Fink.

Bruce Fink (1861-1927) was a giant in North American lichenology. He was the first person to write a comprehensive lichen flora of a large part of North America (The Lichen Flora of the United States, published posthumously in 1935) and one of the first to argue that lichens are dual organisms. As a side note, Fink was an ardent anti-tobacco activist, writing and speaking on the ill effects of its use. Brought on to serve as Chair of the Department of Botany at Miami University of Ohio, he stayed there from 1906 until his death 21 years later. The Consortium contains just over 20,000 Bruce Fink specimens, about 1500 of them from Ohio. The most common of our dust lichens, Lepraria finkii is named for him. The photo is courtesy of the Harvard University Herbaria Botany Libraries, Cambridge, MA. as published in Mercado-Diaz, Joel and Santiago-Valentin, Eugenio. (2010). Lichenological Studies in Puerto Rico: History and Current Status. Harvard Papers in Botany. 15. 93-101.

Portrait of Bruce Fink (1861–1927) from December 27th, 1900.

Save for a brief reference to Lobaria amplissima in Lichens of North America in connection with its association in Europe with some other lichen, this taxon is not included either in that work or in Keys to Lichens of North America: Revised and Expanded. Moreover, the North American herbaria that are members of the Consortium collectively have many more (1777) European specimens of it than they do North American ones. E.E. Bogue, in an 1893 article “Lichens of Ohio” published in the Journal of the Cincinnati Society of Natural History states that S. amplissima is found “On trunks, common.” It’s not clear to me if amplissima is a legitimate taxon so rare as to warrant exclusion from Brodo’s keys, or whether the material is actually represented within a different Sticta, or perhaps one of the related genera such as Lobaria, Ricasolia, Pseudocyphellaria, or Nephroma. If any readers have insight on this (or any other of these old lichen records) please share them with me for use in the forthcoming online version of this article.

Pannaria leucosticta = Fuscopannaria leucosticta (Tuck.) P. M. Jorg. “rimmed shingle lichen,” is represented by 968 North American specimens on the lichen portal. It is a large subfoliose squamulose lichen found mainly on bark, but occasionally on mossy rocks. Eight are from 3 counties in Ohio. No Ohio collections were made after 1962, when Don Flenniken collected it from Washington County.

Sticta quercizans = Ricasolia quercizans (Michx.) Stizenb. Until recently referred to as Lobaria quercizans Michaux, there are 3463 specimens of this “smooth lungwort” from North America, including 60 Ohio distributed among 19 counties. An Appalachian-Great Plains region lichen, it is recognized by the large size, gray color, and smooth surface. Until like…yesterday…the most recent Ohio record showing on the portal is a 1986 collection made by Ray Showman in Hocking County. But look at THIS! (Link to exciting finding by Shaun Pogacnik).

Sticta pulmonaria = Lobaria pulmonaria (L.) Hoffm.

There are 7814 North American CNALH portal specimens of “lung lichen,” of which 47 are from Ohio (23 counties). The most recent one shown on the was made in 1932 by W.B. Cooke from Highland County.

Lobaria photographed in Maine.

Peltigera horizontalis (Hudson) Baumg. There are 1822 North American records for “flat-fruited pelt,” among which 23 are from the Buckeye State (11 counties). The most recent record is from 1972, by Ray Showman, who found it in Gallia County. Distinguished by its horizontal apothecia, when sterile (as Ohio specimens frequently are) it is indistinguishable from the upright-fruited P. polydactylon. In The Macrolichens of Ohio, Showman and Flenniken describe this lichen as “widely distributed ibn the U.S., primarily in mountainous areas; scattered in Ohio; usually on soil, rarely on decaying wood or soil over rock.”

The three lichens in the lower third of the panel are among the few (< 10 percent) of lichens that have a cyanobacterium, not a true alga, as their primary photobiont. These oddities include the gelatinous lichens composed of the so-called jelly lichens (genus Collema) and jellyskin lichens (Leptogium) which have a gummy consistency caused by swelling of a polysaccharide matrix surrounding the cyanobacteria colonies. The other common lichens that have a cyanobacterial photobiont are the pelts, that is, members of the genus Peltigera. Not at all gelatinous; their texture and outward color are not very peculiar except that a cross-section shows a darker photobiont layer than the grass-green one seen in other stratified lichens. They are remarkable lichens, though: very large, loosely attached, and found mostly on soil, which is an odd location for broad-lobed foliose types.

Peltigera polydactylon (Necker) Hoffm. There are 1829 North American records for “many-fruited pelt” in North America, 45 of which are from our happy home state, showing up in 20 counties. The most recent collection was by Shirley Tucker, who encountered it in 1968 at Crane Hollow in Hocking County. This pelt has a similar distribution and ecology to its look-alike P. horizontalis.

Leptogium pulchellum = Collema pulchellum Ach. There are 433 North American records on the portal for “blistered jelly lichen, “10 of which are from the state that, as the old pun goes, “is round on the sides and high in the middle” (6 counties). The most recent are 3 from Clermont County during the years 1929-1932 but without any collectors specified; prior to that we have a Bruce Fink sample obtained in 1913 from Peebles County. It is said by Brodo et al. in Lichens of North America to be common on the bark of poplars and other trees, alongside a distribution map showing it to be concentrated in the southeast U.S. but absent from Ohio. Moreover, this taxon is missing from The Macrolichens of Ohio. The species is distinguished from a more well documented Ohio species, C. nigrescens, by a very technical microscopic feature –the shape of the cells in a specific layer of the apothecium. This could be a case of mistaken identity.

Very large-lobed, loosely attached, with distinctive patterned ridges, and thus among the most easily recognized of all lichens, “lung lichen” was once widely distributed across Ohio, but no more. Ditto for several of the others on this panel. Why are they gone from Ohio? It’s certainly due to a multiplicity of factors that prevailed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries: air pollution and disturbance of old-growth forests. Now that conditions are better for them to grow, perhaps only a lack of propagules is keeping them from reestablishing themselves While eventually a warbler, thrush, or vireo might fly in from the north woods with a little piece of some lungwort on its foot, these might be good candidates for deliberate reintroduction.

The Parmelia Panel

–a list of the specimens–

Parmelia caperata = Flavoparmelia caperata (L.) Hale

Parmelia perlata (= Parmotrema perlatum (Hudson) M. Choisy

Parmelia perforata = Parmotrema perforatum (Jacq.) A. Massal.

Parmelia tiliacea = Parmelina tiliacea (Hoffm.) Hale

Parmelia crinita = Parmotrema crinitum (Ach.) Choisy

Parmelia olivacea = Melanohalea olivacea (L.) O. Blanco et al.

Physcia adglutinata = Hyperphyscia adglutinata (Florke) H. Mayrh. & Poelt

Physcia aquila detonsa Tuck. = Physcia detonsa (Fr.) Nyl.

Physcia stellaris (L.) Tuck. = Physcia stellaris (L.) Nyl.

The Graphis Panel

–a list of the specimens–

Graphis scripta = Graphis scripta (L.) Ach.

Arthonia spectabilis = Arthothelium spectabile A. Massal.

Arthonia punctiformis = Arthonia punctiformis Ach.

Endocarpon miniatum = Dermatocarpon miniatum var. miniatum (L.) W. Mann

Acolium tiglare (Acolium tigilare misspelled) = Calicium tigillare (Ach.) Pers

Verrucaria muralis = Verrucaria muralis Ach.

Pyrenula glabrata = Pyrenula glabrata (Ach.) A. Massal.

Pyrenula nitida = Pyrenula nitida (Weigel) Ach.

Pyrenula gemmata = Acrocordia gemmata (Ach.) A. Massal.

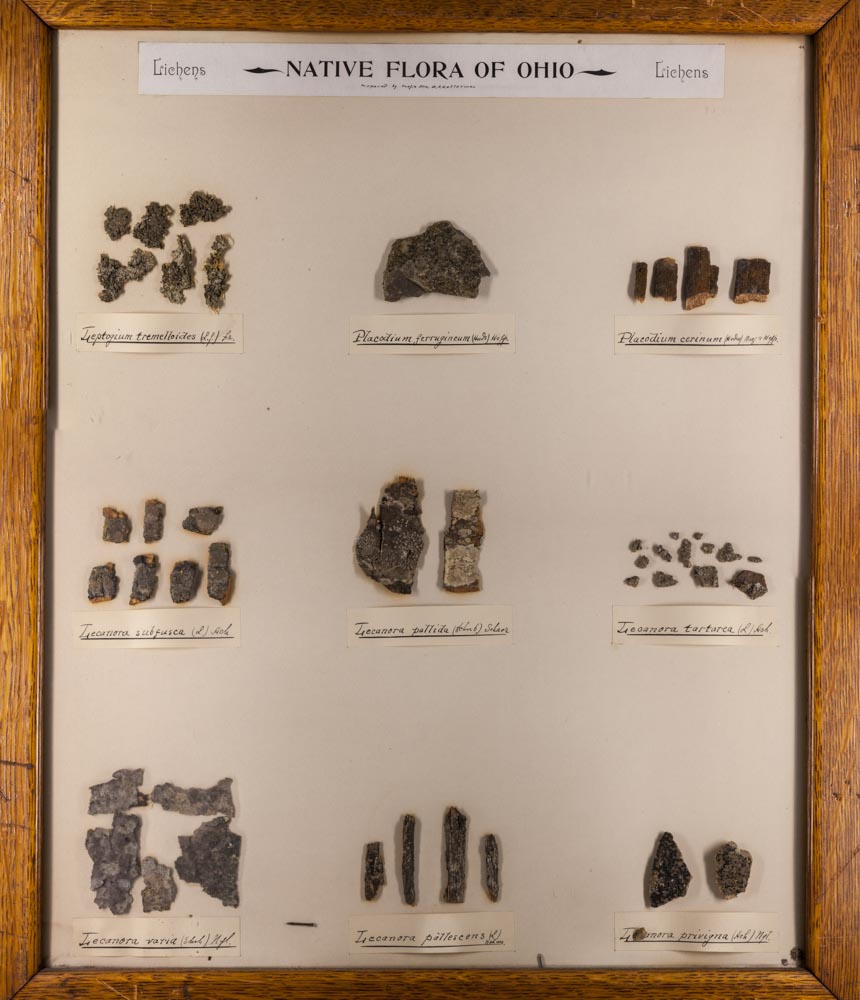

The Lecanora Panel

–a list of the specimens–

Leptogium tremelloides = Leptogium cyanescens (Rabenh.) Korber

Placodium ferrugineum = Blastenia ferruginea (Huds.) A. Massal.

Placodium cerinum = Caloplaca cerina (Ehrh. ex Hedwig) Th. Fr

Lecanora subfusca = Lecanora allophana Nyl.

Lecanora pallida = Lecanora pallida (Schreb.) Rabenh.

Lecanora tartarea = Ochrolechia tartarea (L.) A. Massal.

Lecanora varia = Lecanora varia (Hoffm.) Ach.

Lecanora pallescens = Ochrolechia pallescens (L.) Körb.

Lecanora privigna = Sarcogyne privigna (Ach.) A. Massal.

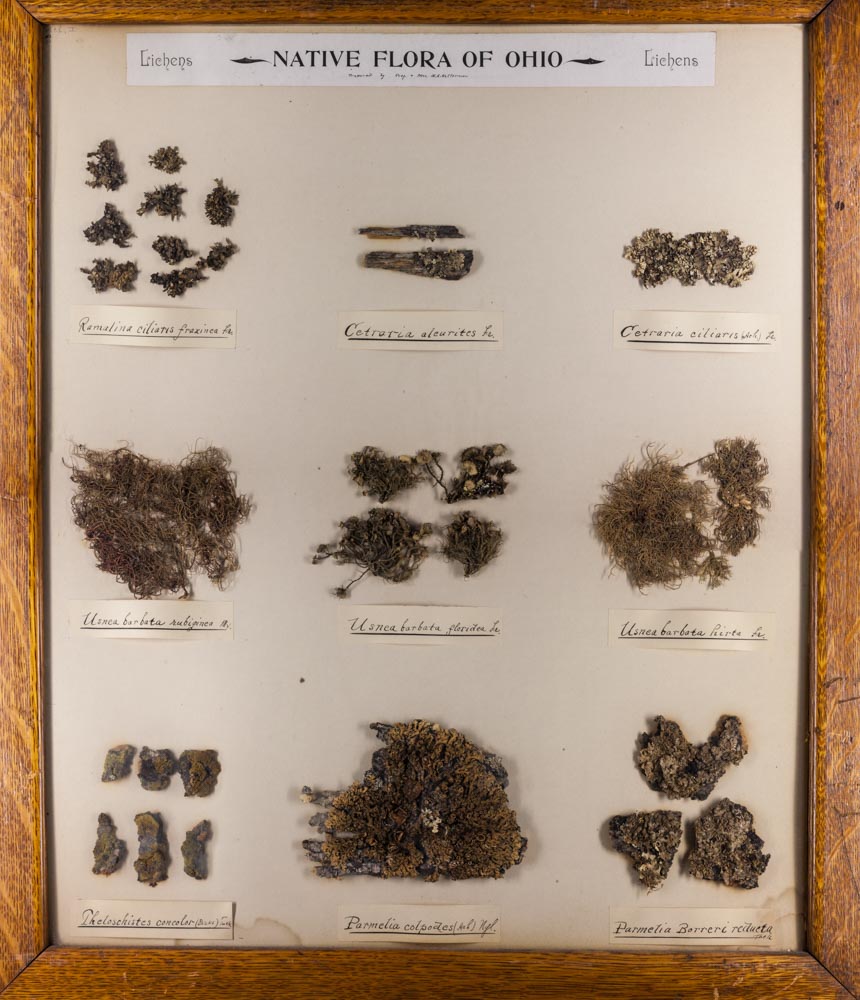

The Ramalina Panel

–a list of the specimens–

Ramalina ciliaris fraxinea = Ramalina fraxinea (L.) Ach. (probably)

Cetraria aleurites = Imshaugia aleurites (Ach.) S. F. Meyer

Cetraria ciliaris = Tuckermanopsis ciliaris (Ach.) Gyeln.

Usnea barbata rubiginea (My.) Usnea strigosa subsp. rubiginea (Michaux) I. Tav.

Usnea barbata floridea = Usnea florida (L.) F. H. Wigg.

Usnea barbata hirta = Usnea hirta (L.) F. H. Wigg.

Theloschistes concolor = Candelaria concolor (Dickson) Stein

Parmelia colpodes = Anzia colpodes (Ach.) Stizenb.

Parmelia Borreri rudecta = Punctelia borreri (Sm.) Krog

Bob Klips

Note: The introductory portion of this article draws heavily on a 2018 blog post the author made for OSU’s Museum of Biological Diversity that can and be accessed at https://u.osu.edu/biomuseum/2018/01/17/a-snapshot-of-ohio-lichen-diversity-125-years-ago/.